Change in Brain Structure Found on MRI Scans in 1 Pompe Type

Damage seen in classic infantile Pompe, but not late-onset form

Written by |

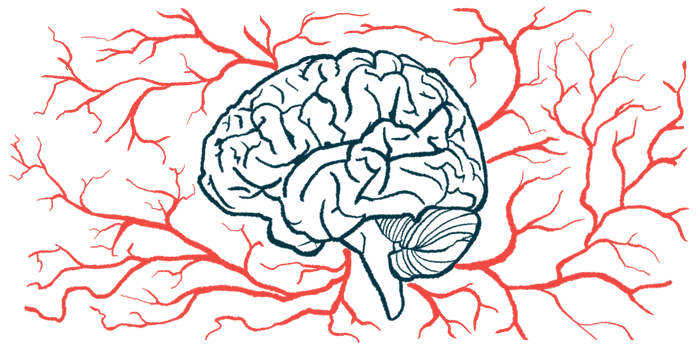

MRI scans of people with classic infantile Pompe disease showed a change in the microscopic structure of certain brain regions — but no damage was seen in patients with the late-onset form of the disease, a new study reports.

“We conclude that, while no deviations from typical neurodevelopment were found in late-onset patients, classic infantile Pompe patients showed quantifiable, substantially altered [brain] white matter microstructure,” the researchers wrote.

The team of scientists used an MRI technique called diffusion tensor imaging, or DTI, to look for damage to the brain’s white matter, which houses the long, wire-like fibers that nerves use to connect with each other.

“DTI holds promise to monitor therapy response in future therapies targeting the brain,” the scientists wrote.

The study, “Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain in Pompe disease,” was published in the Journal of Neurology.

DTI technique may help detect change in brain structure

Historically, most babies born with the classic infantile form of Pompe disease have not survived past infancy due to heart disease and/or respiratory failure. However, the advent of enzyme replacement therapies (ERTs) — medications that administer a working version of the enzyme whose deficiency causes Pompe — has dramatically improved survival outcomes.

Available ERTs can get the enzyme to muscle and heart cells; however, they cannot get into the brain. As more and more children with infantile Pompe are surviving longer and growing up, researchers are working to understand the consequences of the disease on neurological development and cognitive functioning.

Here, a team used MRI imaging to assess the brains of 12 classic infantile Pompe patients, ages 5–20. They also analyzed the brains of 18 people with late-onset Pompe, ranging in age from 11 to 56.

All patients were on ERT, except for three late-onset patients who did not have any muscle involvement at the time of assessment. Median ERT duration was 7.1 years in participants with classic infantile disease and 10.2 years in late-onset patients.

To examine the brain’s white matter in these patients, the scientists specifically used the MRI technique diffusion tensor imaging, or DTI. (Brain tissue can be broadly divided into two types: white matter and grey matter, which contains the bodies of nerve cells.)

Compared with reference data from a population-based study, children with classic infantile Pompe disease showed abnormalities in all assessed white matter tracts. Specifically, a measure called fractional anisotropy was significantly lower, while another measure called mean diffusivity was significantly higher.

These differences indicate that “white matter microstructure is disrupted” in these patients, the researchers said, noting that this could reflect processes like inflammatory damage or the breakdown of myelin, a fatty covering around nerve fibers that helps them send electric signals.

The team also found that differences in microstructure on white matter were associated with overall structural changes detected via MRI.

In contrast, most of the late-onset patients had “a completely normal structural MRI,” the researchers reported. None of the few late-onset patients who had white matter abnormalities showed lesions as extensive as was typical for the classic infantile group. There were no associations between MRI outcomes and age among these patients.

Overall, the findings from the late-onset patients were “similar to the stage of relative stability found during normal aging,” the researchers noted, though they added that caution is needed in interpreting these results due to the small sample size and the lack of direct comparison subjects.

In addition to shedding further light on neurological development in Pompe, the researchers said this study supports the use of DTI as a way to measure the effectiveness of experimental Pompe treatments targeting the brain.