Motor neuron dysfunction may predict poor response to ERT

Findings underscore importance of testing for nerve cell impairment

Written by |

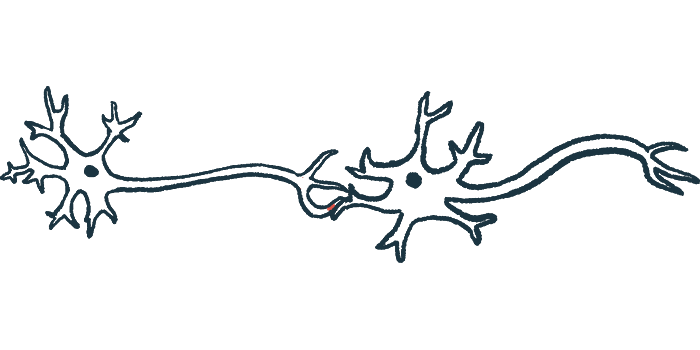

Some children with Pompe disease have dysfunctional motor neurons — the specialized nerve cells that control movement — in addition to muscle abnormalities, a new study highlights.

Findings from the small study suggest that patients with motor neuron impairment may be less likely to see clinical benefits from enzyme replacement therapy (ERT).

“Our results show that [motor neuron damage] may coexist with muscle involvement at disease onset and may be a marker of poor response to ERT and severe outcome,” researchers wrote in “Motor outcomes in patients with infantile and juvenile Pompe disease: Lessons from neurophysiological findings,” which was published in Molecular Genetics and Metabolism.

Pompe disease is caused by mutations that disrupt the function of the acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) enzyme. ERT is a treatment strategy wherein a functional version of the enzyme is administered.

Normally, GAA breaks down the complex sugar molecule glycogen. In Pompe disease, the molecule builds up to toxic levels in cells. Pompe disease mainly affects muscle cells, which use glycogen as a form of energy storage.

ERT and motor neuron dysfunction

In this study, scientists in France reported on the clinical outcomes for 20 children with Pompe disease who were treated with ERT. All were tested to assess the electrical activity in their muscle cells and motor neurons. Twelve children had infantile-onset Pompe disease (IOPD), which features symptoms that develop in the first year of life. These 12 started on ERT after beginning to have disease symptoms.

Among them, the scientists saw two who had a particularly poor response to ERT. Neither was ever able to walk. When they were diagnosed at the initial evaluation, they were found to have impaired motor neurons.

The study also included four children with IOPD who started on ERT before developing obvious disease symptoms because they were diagnosed very early through newborn screening or testing due to family history. These four all were able to walk as toddlers, but one lost that ability at age 3. It was about that time the child was found to have motor neuron impairment.

The remaining four children had late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD), with symptoms developing after the first year of life. Despite ERT treatment, one had a notable deterioration in motor function at around age 10 and was found to have motor neuron impairment at around the same time.

“The two patients presenting with [motor neuron dysfunction] at diagnosis had the most severe outcome. For other patients, significant motor deterioration and loss of walking were associated with the development of” motor neuron problems, the researchers wrote.

Some people with Pompe disease can develop an immune reaction against ERT, which is associated with their cross-reactive immunological material (CRIM) status. It has been established as a marker of response to therapy in previous studies. The researchers noted that CRIM status didn’t show a clear association with ERT response among these patients, however.

The findings underscore the importance of assessing for motor neuron dysfunction with Pompe disease, as it may be a relevant marker of treatment response, said the scientists, who also noted the study was limited by its small size and retrospective nature. “Further large and standardized studies are needed to better describe the [motor neuron] outcome of pediatric Pompe Disease and determine prognosis factors,” they wrote.