Brain changes linked to cognitive issues in IOPD patients on ERT

Abnormalities may interfere with brain function, cause cognitive deficits: Study

Written by |

Most people with classic infantile-onset Pompe disease (IOPD) develop brain abnormalities despite treatment with Myozyme (alglucosidase alfa), and these abnormalities are associated with poorer results on cognitive tests.

That’s according to a study, “Long term survival in patients with classic infantile Pompe disease reveals a spectrum with progressive brain abnormalities and changes in cognitive functioning,” which was published in the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease.

Pompe disease is a genetic disorder in which the body cannot produce a functional version of the enzyme acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA). This enzyme is normally needed to break down a complex sugar molecule known as glycogen. Without functional GAA, glycogen builds up to toxic levels in cells, causing damage that drives disease symptoms. Classic IOPD is characterized by symptoms including heart damage that manifest in the first year of life.

Enzyme replacement therapies, or ERTs, are medications that work to deliver a working version of the GAA enzyme to the body’s cells. ERTs are a mainstay of care for Pompe disease, and they can substantially improve survival outcomes for babies with IOPD. Myozyme, sold as Lumizyme in the U.S., was the first ERT approved for Pompe disease.

ERTs limited by inability to cross from blood into brain

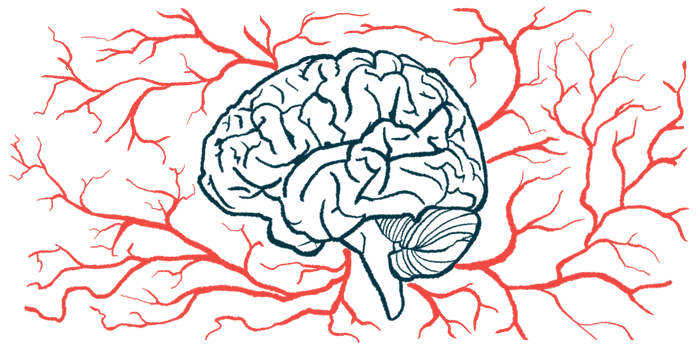

A notable limitation of available ERTs, however, is that none of them are able to cross from the bloodstream into the brain. As such, while ERTs can help prevent toxic glycogen buildup in most of the body, they can’t reach cells in the brain. In recent years, there have been several reports of children with IOPD who develop brain problems despite ERT.

In the new study, scientists in the Netherlands reported outcomes of 19 IOPD patients who received care at their center. As of the most recent assessment, these patients ranged in age from 1.5 to 22.5 years.

Brain imaging, acquired via MRI, was available for 17 of the patients, and many of them had multiple images taken over time. Brain abnormalities were detected in all but one of these patients.

The researchers noted that abnormalities were seen particularly in white matter, which contains the long, wire-like nerve fibers that connect different parts of the brain. These abnormalities tended to follow a pattern, with the earliest changes seen toward the center of the brain, then changes seen near the front of the brain, followed by changes elsewhere.

“We found that brain MRI abnormalities progressed in a characteristic pattern, spreading throughout the brain,” the researchers wrote.

To assess cognition, the patients underwent standardized assessments to calculate their intelligence quotient (IQ), which is a numeric representation of cognitive ability based on age. Statistical analyses suggested IQ and related measures tended to worsen slowly with age in these IOPD patients.

“Although the yearly decline seems small, we think it is not only statistically significant, but also clinically relevant, especially when measured over a longer period of time,” the researchers wrote, noting this finding “stresses the importance of repeated cognitive assessment throughout childhood and adolescence” for clinicians caring for people with IOPD.

IQ scores associated with brain abnormalities on MRI

In further statistical analyses, the researchers demonstrated significant associations between IQ scores and brain abnormalities seen on MRI. For every additional brain region where abnormalities were found, total IQ scores decreased by an average of four points. Measures of processing speed — the time it takes a person to take in information, process it, and then react to solve a problem or complete a task — and verbal IQ also tended to be worse in patients with more substantial brain abnormalities.

“Patients with white matter abnormalities, showed a decline in their cognition with increasing age. This decline was significantly correlated with the further progression of brain abnormalities,” the researchers concluded.

The scientists interpret these data to suggest the abnormalities are probably interfering with brain function to cause cognitive issues. Although these associations were seen in the group overall, there was a lot of variation from patient to patient, they noted.

Additional larger studies are needed to more fully map out how IOPD may affect the brain, the researchers wrote, adding their findings underscore the need for new IOPD treatments that can cross from the blood into the brain.